News

I look out of our windows, and I see Gibsons Harbour and the Paisley Islands – part of the Salish Sea I love and I want to protect. I walk along its shores, I swim in it, and since I am a diver, I have explored it underwater. I fear for it. I do not want us to reach a collective stage in which we appreciate something when we no longer have it. The big threat to our Salish Sea has a name: BITUMEN.

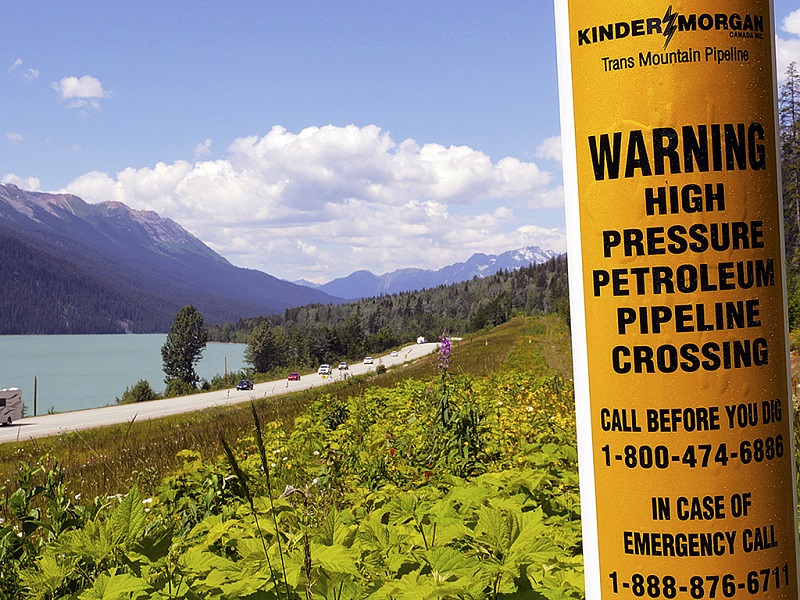

The double threat of a pipeline carrying diluted bitumen from the Alberta tar sands to the coast of B.C. to ship it on large tankers to Asia, and of Kinder-Morgan planning to twin their existing pipeline to Vancouver, tripling capacity from about 300,000 to 900,000 barrels a day, to increase ten-fold the present tanker traffic, decided me to make a film showing the beauty of the Salish Sea – the waters encompassed by Vancouver Island and the shores of mainland B.C. and of Washington state.

For many of us, the images of the destruction and devastation created by the Exxon Valdez and the British Petroleum disasters in Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico respectively have become icons of environmental desecration. Yet, a spill of bitumen on land or at sea would be far more devastating, for bitumen is so viscose and dense that, to flow, it has to be diluted with naphthalene, or other thinning agents. Then, when those agents evaporates, bitumen sinks, making it impossible to clean, as it covers bottom of the sea, or lake, or river, covered with black tar – a black death. It is hard to imagine a product more efficiently designed to destroy the water environment, a toxic waste, first floating to cover a wide surface, including shorelines, and then sinking, to cover the bottom.

I realized, then, that the tar sands in Northern Alberta had to be part of my film on the Salish Sea. So, to work for the protection of the Salish Sea with the tools and skills I have, with my wife, I undertook to participate, along with several hundred others, in the Healing Walk, north of Fort McMurray. It was a trip which left me with strong images and messages of irony, of hope, and of despair.

Lyonoor – my wife- and I had not planned on spending the beginning of the summer holidays driving at an unrelenting pace to Fort McMurray, covering 1,700 km in two days. In the first instance of irony of this endeavour, we clocked close to the same number of kilometers on this trip that we drive in an entire year, and each time we filled up our tank, we knew we were contributing to the profits of the very oil companies we want to discourage from expanding.

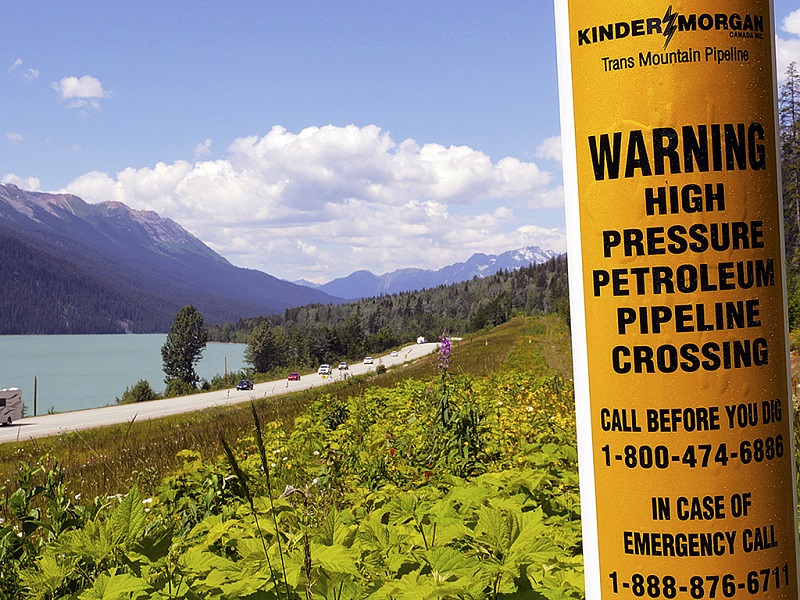

Our route, along the North Thompson River, and Fraser River, through Jasper National Park, followed the existing Kinder Morgan pipeline. The pumping stations on the side of the road were just meters from the rivers, lakes, and streams we passed. Often, there were lines of cars parked along the highway, with tourists photographing grizzly bears, elk, and mountain sheep. The hotels and motels in the small towns we passed rely on those tourist dollars.

We could not stop. We had to arrive at the Indian Beach campsite, an hour away from Fort McMurray, in time for the Healing Walk.

By nine o’clock at night on July 4, we had pitched our tent by the lake. Now, we could prepare ourselves for the events of the following two days: the fourthannual Healing walk, organized and hosted by the Athabasca Chipeyewayn First Nation and by the Keepers of the Athabasca. The tents in the campsite looked like a multicoloured patchwork quilt with random patterns of shapes and colours. We were on the 57degree parallel, and even inside the tent, it was fairly light until 11:00 pm. We began to meet and greet the hundreds of participants who braved the rain, the mud, and the mosquitoes in that un-serviced campsite. Among those we met, there were people from Texas and California, from Idaho and Washington State, from B.C, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Quebec, and, of course, from all over Alberta. There were people of all ages and backgrounds, and First Nations members from across Canada came to participate. There were no protest signs or slogans. This was not a protest; it was a healing event. The following days there were powerful, sometimes emotional speeches, but what words, what images, what sounds will stay with me?

The woman and the teepee: First, we smelled the fire; then, we saw the teepee, golden and shadowy in the fire light. The following evening, a woman sitting outside the teepee called us two to see the child she was breastfeeding, the child that had been born inside that teepee the previous night, the night we arrived. In the night, sleeping beside Gregoire Lake, I heard the loons cry, and the distinctive splash of beaver tails

.

The mud and the rain: It rained constantly on Friday, July 5, while we attended workshops under tents. Everybody’s shoes were caked in mud. The elders who opened the ceremonies before the workshops did not complain about the rain, but blessed it instead for the cleansing it provided.

What I heard: While waiting for a workshop to begin, I overheard a conversation behind me. A man was saying he had flown from Vancouver to Fort McMurray the day before, and that he had expected to see the tar sands from the air just before landing, but he did not see them. Someone told him there was an arrangement between the authorities and the airlines so that the tar sands could not be seen from the flight path - an interesting optical consideration, if true.

The following day, during the walk, a man walking behind me was telling his companion that he had worked for five years in the tar sands. Now, he was walking.

Patience, perseverance, priorities: The presentation on litigation outlined some of the legal struggles and court cases of, among others, the Bear lake Cree Nation. I gained a new respect for those who, with very limited resources have to reduce their budget for health and education to pursue court cases in which corporations and/or governments with much greater means argue their rights to disregard their responsibility for the environment or for the rights of the people who live in that land. Further, I heard speakers talk of strange deformities, lesions, and cancers appearing on fish and game that they had relied upon for their food source for thousands of years.

The young people from Aamjiwnaang: On Saturday, July 6, in the morning, we all piled onto school buses for the one-hour ride to Crane Lake Park, where the fourteen km. walk would start. On the bus, we met several young people from near Sarnia, Ontario. They had come in part due to their concern for their own home and their own people. Their First Nation is surrounded by large petrochemical processing complexes. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the male/female birth ratio has become very distorted. Whereas normally an approximately equal number of males and females are born, in their community, the female births comprise approximately two-thirds of the total number of births. The Aamjiwnaang were featured in the documentary The Disappearing Male.

A speaker, Vanessa, said that the rate of miscarriages in her community was 49% above the average for that of the rest of  Canada. She said, “You are fighting for something more valuable than oil, and that is, the blood of our future generations.” How could I forget their eyes and voices as they told us about their home in Sarnia, completely surrounded by petro chemical industries?

Canada. She said, “You are fighting for something more valuable than oil, and that is, the blood of our future generations.” How could I forget their eyes and voices as they told us about their home in Sarnia, completely surrounded by petro chemical industries?

Canada. She said, “You are fighting for something more valuable than oil, and that is, the blood of our future generations.” How could I forget their eyes and voices as they told us about their home in Sarnia, completely surrounded by petro chemical industries?

Canada. She said, “You are fighting for something more valuable than oil, and that is, the blood of our future generations.” How could I forget their eyes and voices as they told us about their home in Sarnia, completely surrounded by petro chemical industries? The smell of tar, the sound of shooting: The fourteen-kilometer walk along the Syncrude Loop carried us along the tailings pond and the processing plants. As we began walking, we were startled by constant shots, as if we were by a shooting range. Those were the shots from the guns on the enormous tailings pond, to prevent birds from landing on its contaminated waters.

From about 50 km south of Fort Mc Murray, and all along the walk on the Syncrude Loop, we smelled petro-chemicals, as if a nearby road was being surfaced. Depending on the wind, the smell was stronger or fainter. I suppose that, after a while, people get used to it and they do not smell it any longer.

The crosses: Along the highway, on the way to Fort Mc Murray, and along the Syncrude Loop, we saw the many crosses – metal, rusted crosses, usually with the helmet or other mementos of the dead men hanging on them. The highway, wide, flat, and straight, is called locally, the highway of death. When workers finish their shift, they would rush away from this place, to family and friends, taking high risks. There was a feeling of melancholy and sadness over the land, filled by the beat of heavy trucks, and the fumes of tar.

The pain of the elders as they walked: The elders led the walk, and all the other participants followed. It would have been disrespectful and against protocol to forge ahead. Only the photographers and film crew could be in front to film. The elders – one of them was Amy Marie George, the daughter of Chief Dan George- walked slowly, often aided by canes, and as the walk progressed, many of them were in pain. Did their faces, as they looked on the massive excavations and gigantic machinery, reflect more than physical pain?

The support of the truck drivers: I had expected a somewhat antagonistic reaction to the walk participants from the workers on the site. From the elders at the beginning to the last stragglers at the very end, the hundreds of marchers formed a very long line. Many of the big trucks passing us would begin playing their horns before they passed us, and all along the line, for a long time, sometimes waving at us and giving us the V sign.

Wrong Way: That road sign, with the tar sands, the machinery, and the processing plants in the background, said it all.

The polarization and the contradictions: Several of the speakers acknowledged the divisions within their communities, as they pointed out both the economic dependency on the tar sands and the need for protecting the environment. Several called for slowing down the pace of development. I reflected on the economic impact of an oil spill – the damage to tourism, to farming and cattle, to the fisheries. What price tag does the damage to health carry, our health and the health of the planet?

“We can make a killing!”: One speaker, Tzeporah Berman, told of meeting with a government official about the impact of the tar sands. He told her, “But we can make a killing!” That is exactly what the industry did. During the walk, a participant received a text message about the disaster at Lac Megantic. Killing was the precise word. The petroleum industry had made a killing.

“Rare cancers”: Another speaker, Lionel Lepine, from Fort Chipeyewayn, told me about the incidence of rare cancers in his community, and of the vast deposits of high grade uranium ore beside the tar sands, and of the exploration, and of plans to open uranium mines soon. What legacy will be left in these communities?

The children: There were many children at the campsite and on the walk. They played with each other and walked along. The walk was long. It was tiring. There was no whining or complaining. The children did their part, for this was their future. What legacy will we leave them?

My last image: As I write this, I look out of my window, at Gibsons Harbor and the Paisley Islands, at the sea.